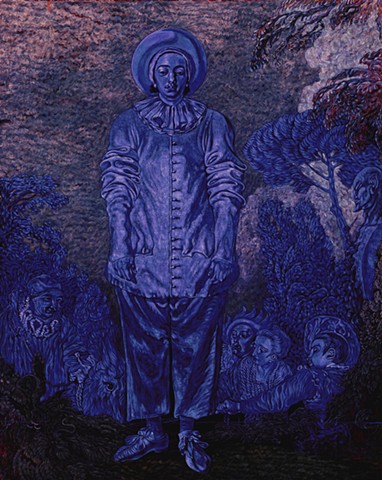

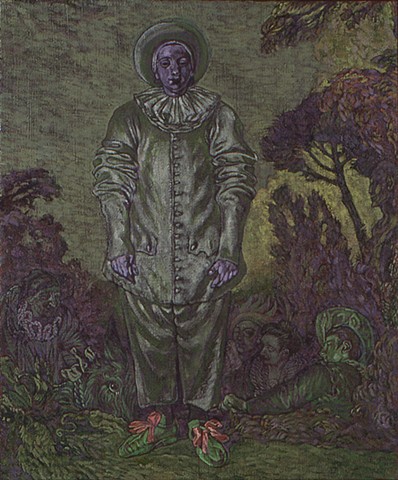

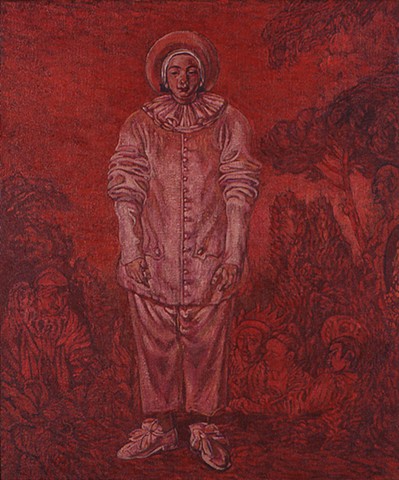

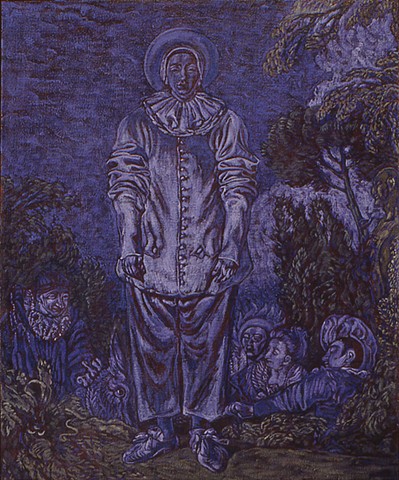

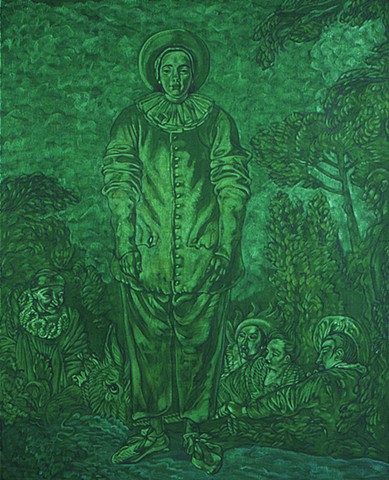

Gilles 1994 - 1998

When I started this project I was teaching a painting seminar about the Death of Painting.

In 1994 I went to France and saw sixteen versions of Claude Monet's "Rouen Cathedral' at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Rouen, a series he did in 1892 - 93, a hundred years earlier. I also encountered my first Yves Klein blue monochrome painting at the Centre Pompidou, which had been painted in 1960. On a previous trip to Paris I had fallen in love with Jean-Antoine Watteau's “Gilles” at the Louvre, finished in 1720, which may have served as a shop sign for a café.

In my research on Yves Klein, I was taken up by his persona of the Dandy; he'd moved the legacy of Beau Brummel to the 20th Century. I was quite envious of the younger male painters in my own milieu who seemed able to take up abstract painting without a qualm. Dandies themselves, they smartly took up a critique of the monochrome, weaving in references to pop culture, while making attractive, decorative work. They got to have their cake and eat it too. I’d trained as a formalist fifteen years earlier, but like many artists in the heady 80s, I had eschewed a conservative practice that didn't take up the political.

The seriality of Monet's project connected to the seriality of Yves Klein's. Yves Klein's performative figure seemed to connect to Gilles, the consumptive clown/artist. Both died young. Although known for his blue paintings, Yves Klein dealt with all the primaries. His paintings were a reiteration of Rodchenko's red, yellow and blue monochromes, which in 1921 declared the death of painting. The first time this sentiment may have been uttered was in 1839, when the French painter Paul Delaroche was asked to prepare a committee report on the invention of the Daguerreotype to the French government. My own seriality was an attempt to reconcile my mixed feelings about all of these things.